The accidental comedian

The OED defines ‘accidental’ as: happening by chance, unintentionally, or unexpectedly.

I don’t have any more accidents than the average man – I’ve still got all my fingers and toes – though there have been some good ones: as a child I’m pedalling my bike along a path in an army camp in Cyprus, when a wasp flies into my eye, panics, and stings me – it’s exceedingly painful but leaves a very pleasing star shape in the middle of my iris that lasts for more than a week (very David Bowie); playing mountaineers in a tree on the same base, for reasons unknown I ‘belay’ the safety rope around a high branch, secure it around my neck, and promptly fall out of the tree – only the swift action of the soldier who lives next door saves me from certain death (hanging is abolished the following year and there are no further incidents of this kind); driving my BMW R65 motorbike with its distinctive cylinders that stick out on either side I misjudge an overtaking manoeuvre and get trapped between two cars moving fast in opposite directions – I lose both cylinder heads but come out of it unscathed (cf. the opening motorbike sequence in Guest House Paradiso).

But most of my career happens by chance, unintentionally or unexpectedly. Accidental defines much of my life, and most definitely describes the way I become a comedian.

Many ambitious young actors I meet these days seem to have their lives planned out. They’ve got a good agent from their final year show at drama school, and now they’re going to do theatre for two years – the National or Royal Court, not the ‘ghastly’ commercial stuff – then get a good supporting role in a drama series, and go off to LA for the pilot season . . .

I’ve never planned my life further than a few weeks or months ahead. Even now, when a job is coming to an end and people ask ‘what are you doing next?’ I generally answer, ‘I’m currently unemployed for the rest of my life.’ I say it as a joke, but it’s disappointingly true. At the moment of writing it’s happening again next week.

Certainly, fresh out of uni, the general state of play is to wake up in the morning and see what happens that day.

Of course I have preposterous dreams: I will play Hamlet at the RSC; I’ll be the new Malcolm McDowell or John Hurt; I’ll be in the next Nic Roeg or Mike Leigh film. But these things are out of reach because I don’t even have an agent. No one in the world of theatre, television and film knows that I exist.

No one, that is, except Rik.

If you’d asked both of us what we intended to be when we arrived at Manchester we’d have both said ‘actor’. I tell a lie, Rik would have said ‘sex god’, but he’d have wanted to become a sex god through being an actor – like James Dean or Steve McQueen.

There’s a Wikipedia rumour that we used to go around in our final year shouting, ‘We’re going to be stars! We’re going to be stars!’ But this is another of those dreadful Chinese whispers, and is in truth a story about Paul Bradley.

Another of the London-Irish set, Paul’s witty and jokey. He likes drinking, rugby, larking about, and . . . doing impressions of what he imagines Ian McKellen and Derek Jacobi are like in their everyday lives.

It’s a time when people still sell the communist newspaper the Morning Star on the steps of the Student Union building every day.

‘Morning Star!’ the news vendor will shout as we climb the steps.

‘Morning love!’ Paul will reply, doffing his imaginary trilby. ‘No time for autographs today, I’m afraid.’

It’s a particularly stupid gag that amuses me every time. And if I spot Paul in the vicinity I will wait at the bottom of the steps and go up with him just to hear it again. Perhaps I like it so much because, although it’s a joke, it epitomizes the kind of ‘comical luvvie world’ I seek to enter. It feels like such a joyful world.

Rik, Paul and I all think we’re heading towards a life in the theatre. We joke that the last term should really be focused on how to order a gin and tonic at a crowded bar on a first night, and the three of us invent a kind of music hall patter song which we sing to the tune of ‘The Laughing Policeman’:

Theatre, theatre, theatre, theatre, theatre, Peter Hall

Theatre, theatre, theatre, theatre, Lauren Bacall

Theatre, theatre, theatre, theatre, Tommy Court-e-nay

Theatre, theatre, theatre, theatre, Laurence Ol-iv-ier

You will have spotted that there are no jokes in the lyrics – well done – no, the fun comes in performing it with knowing winks and nods which imply that all these people are our closest theatrical chums.

But we find ourselves being steered towards comedy, firstly by chasing the Variety contracts at The Band on the Wall, and perhaps secondly by the way we’re perceived by our fellow students. Every group finds its natural comedians, and while others explore more serious means of self-expression – I particularly remember a nude version of Marlowe’s Edward II set in a cage – we will happily take the piss.

We also have very few options: we don’t have Equity cards and these bloody Variety contracts seem to be our only route in. But even they are proving elusive – how can we get them? Well, by being ‘comedians’.

I’ve said that Rik and I were always desperate for a laugh, but gagging for a laugh doesn’t necessarily mean you want to be a comedian. Every single member of The Beatles was a very funny guy, but they never wanted to take up comedy as a career. Judi Dench, one of our greatest tragedians, is by all accounts one of the funniest people on the planet, who laughs all day long even when she’s making rather bleak films like Philomena or Belfast, but she’s never professed herself to be a comedian. My youngest brother Alastair was always thought of as the joker in our family but he ended up driving big trucks in Australia.

Yet Rik and I leave university more as comedians than as actors.

We’re not thinking in terms of ‘career choice’ – indeed the idea of a ‘career’ seems frankly laughable at the time (and still does) – we’re just taking the line of least resistance. It’s the only line we’ve got.

The word comedian is going through a strange time in the 1970s.

To some it’s a bit of an insult, meaning someone who’s not quite all there, who’s not taking things seriously enough. Policemen will say, ‘Oh, we’ve got a right comedian here.’ In fact they’re still saying it in 1981 when I’m arrested in Soho for being drunk (berserker).

I’m many sheets to the wind and I’m taken to the cop shop in Savile Row – though frankly they’re no better dressed than policemen elsewhere – and when taking down my particulars they ask for my profession and I say: ‘Comedian.’

‘Oh, we’ve got a right comedian here,’ they say, rolling their eyes.

‘Yes, that’s what I said,’ I say.

The trouble with playing to an audience of policemen in a police station is that they have the ultimate heckle – they lock me in a cell for the night.

To others the word comedian means the TV show The Comedians on which a series of club comics, mostly wearing dinner jackets and bow ties, tell jokes. These jokes are along the lines of ‘three men went into a pub . . .’ or ‘a fella goes in to see a psychiatrist . . .’ It’s frankly unexciting stuff, any of the jokes could be told by any of the comedians, and there’s an unhealthy whiff of racism and misogyny to it.

The stereotypical live comedian when we leave university in 1978 is a fat, white man in a DJ who tells jokes about his mother-in-law, Irish people, and people with a darker skin tone than his. He finds Pakistanis particularly hilarious, and homosexuals are a scream. It’s not really comedy at all, it’s more sharing insecurities about things with people who are similarly affrighted.

This isn’t in any way what we’re about, and we don’t see how we can enter this world of live comedy, which at the time is centred around the working men’s clubs, and places like the Batley Variety Club. We ring a couple of variety agents but I don’t think they like our middle-class accents.

Another route is the folk club circuit where Billy Connolly and Mike Harding both cut their teeth before moving on to bigger things.

And the third route is to go to Cambridge University and get into Cambridge Footlights, who seem to have a direct line to the BBC Comedy Department, but neither of us is brainy enough.

There had been a fourth route. It’s amazing how many post-war comedians started off as conscripts performing in little concert parties for groups like ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association): Benny Hill, Kenneth Williams, Spike Milligan, Stanley Baxter, Terry-Thomas, Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers, Frankie Howerd, Denis Norden, Eric Sykes, Tony Hancock, Harry Worth, Tommy Cooper and Jimmy Perry, the creator of Dad’s Army.

We aren’t working class enough, folky enough, or brainy enough. And we haven’t been to war.

Manchester University is one of the so-called ‘red-brick’ universities – one of the nine universities founded in the nineteenth century in industrial cities like Liverpool, Leeds and Birmingham. They’re called red-brick because they’re not made out of honey-coloured limestone like the buildings at Oxford University, nor are they endowed with the stained-glass windows and fan-vaulted ceilings of Cambridge University – they are more simply fashioned out of bog-standard red bricks. It’s the cheaper and less prestigious alternative, perfect for people like us.

We are red-brick comedians. And there aren’t many of us around in 1978. Precisely none, as we see it at the time. And as when leaving school and trying to find a way to become an actor, there isn’t the faintest hint of a career path. Which means we have to invent our own.

So I sit in my study – by which I mean I sit in the cupboard in the hall of the flat I’m now renting in Tamworth, just outside Birmingham. It’s no wider than the door frame, but I’ve managed to cram in a desk and a chair. I write to every single arts centre and student union in Britain, and when I say write I mean I physically type every single letter. There are no computers and home printers yet, and I don’t have a Roneo machine (a Rotary Neostyle duplicator, beloved by schoolteachers, which don’t so much ‘duplicate’ as produce a smudgy, purple ‘impression’).

Our time at uni coincides with the birth of punk, and that DIY spirit is coursing through our veins – who cares about conventional theatre? We will play anywhere, anytime. And in our first year out we play . . . four gigs.

Out of the 400+ institutions I write to only a dozen or so reply, and none of them offer us a gig. We play one date back at Manchester University where the Stephen Joseph Studio charitably invites us to perform, we do another at Bromsgrove College of Further Education where Rik’s dad is a drama lecturer (nepotism), and we do the National Student Drama Festival in Southampton as mature (!) students, where we manage to get another offer of a gig from Hatfield Polytechnic.

‘Here’s three chords, now form a band’ is the famous mantra of the punk movement. We know the equivalent of more than three chords, in terms of comedy I think we know at least four, and one of them might be augmented (almost jazz), and we’ve got a ‘band’, but we don’t know how to make people listen to us (also like jazz).

Gloria Gaynor is top of the charts with ‘I Will Survive’ and that’s basically all we’re doing, surviving. We’re doing dead-end jobs to earn money – Rik’s back living with his parents and working in a meat-packing plant in Droitwich, I’m living in a council flat in Tamworth and working in the Exhaust Pipe Warehouse in Birmingham – and this rather hampers our creativity. We’re living either side of Birmingham, forty miles apart, and have to make do with weekends getting pissed and improvising into a cassette recorder.

He comes over to mine every Saturday. We go to the pub, drink lager with whisky chasers, play pool, and put ‘Revolution No. 9’ by The Beatles on the jukebox several times in a row. After chucking-out time we go back to my flat and the chip pan will swing into action. We press play and record and make each other laugh and laugh and laugh. The next morning we listen back – it’s mostly unfunny gibberish with the sound of kitchen accidents in the background. It’s a painful way to make comedy. It’s not the hilarious profanity of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s Derek and Clive (Live) that we were aiming for: it’s just profanity. We decide we need to be more professional.

So the following year we move to London and book ourselves a ten-date tour of church halls around the capital. It’s a sketch show called The Wart! that includes an early version of the Dangerous Brothers – two psychopaths who think they are light entertainers.

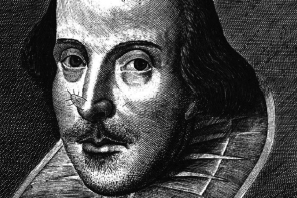

We’re promoting ourselves, hiring the venues, doing our own publicity, sending things to anyone and everyone; there’s a lot of cutting and pasting going on – actual cutting and pasting, not the computerized kind – we try everything we can think of to drum up an audience. The blurb on the handbill reads: ‘Soon the world will be divided into those who missed The Wart! And those who didn’t bother to go at all.’ This ends up being more or less accurate as the average audience is about six people, but one of them happens to be a reviewer from The Guardian. I don’t know what seduces him to come and see it. I’ve written to every single reviewer but he’s the only one that comes. Maybe it’s the handbill which features the 1623 Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare . . . with a huge hairy wart stuck on the end of his nose. Critics love Shakespeare.

He gives us a small but positive review, remarking on Rik’s ‘rubbery-faced intensity’ and describing me as ‘the eternal little man’. Though remembering those phrases again, I’m not sure if it is a positive review . . . but we think it is at the time, and look on it as validation that we are ‘professionals’.

Another member of the tiny throng at a church hall in Kennington is a large, fiery Welshman who’s the manager of a venue called The Tramshed in Woolwich. He’s only recently taken over the organization and he’s a man on a mission to turn it into a place of daring artistic excellence. He wants to create a new kind of cabaret on Friday and Saturday nights and offers us a residency. We grab it.

Should have gone to Egypt . . .

The Tramshed, it turns out, is as much a community centre as an arts centre, and it’s a positive thriving asset to the local area: it’s busy all week long with community events and youth theatre projects and on weekends they create their own fun night out – which attracts quite a few squaddies from the local barracks – a jolly sketch show called Fundation, led by a guy called Joe Griffith, which features, among others, another comedy double act called Hale & Pace.

But the fiery Welshman has taken against Fundation – he considers it too lowbrow – and wants us to replace it (!). He also wants to revolutionize the artistic output and we get bit parts in his production of Macbeth set in Vietnam with soldiers smoking dope through shotguns.

‘I want it to be really relevant, really punk you know – like . . . GREEN HAIR’ becomes a phrase of his that we remember forever. We use it whenever we want to describe something that is catastrophically misguided.

So every weekend he puts on a kind of variety show and we come on in between the jazz band Greenwich Meantune and the speciality act of the week. It’s not our milieu – we’re doing our Sam Beckett piss-takes and the locals and the squaddies want Cannon and Ball. We end up doing the few sketches from The Wart! that work in that environment. We do them over and over again, separating the wheat from the chaff, until we’re basically just doing the Dangerous Brothers.

The Dangerous Brothers are like this: Rik plays Richard Dangerous who looks as demented as Ron Mael, the mad keyboard player from the band Sparks, but on amphetamines. Like Ron he appears to have a hidden agenda but he’s wired, anxious and hyperactive. I play Sir Adrian Dangerous who is fundamentally a berserker – he is furiously violent and out of control. He’s the obvious foot soldier in the relationship, but is too stupid to understand his position. There’s always a suspicion that they are being watched by a higher power – Mr Cooper – and that if they fuck up they will suffer serious consequences, so there’s a frenzied urgency to get everything right. They’re more like hitmen than comedians, but it becomes evident they’ve been sent to deliver a bog-standard cracker joke:

‘What’s green and hairy and goes up and down? A gooseberry in a lift.’

But they never get to tell it in this simple form.

Rik springs onto the stage and shouts: ‘We are the Dangerous Brothers! I am Richard Dangerous! And this . . .’ he says as I rush on after him ‘. . . is Sir Adrian Dangerous!’

At which point I run forward and headbutt the microphone. It not only makes a brilliant sound, but usually bursts from the mic stand and lands in the audience.

They argue and bicker and fight. They’re never stationary. They have enormous problems with logic. The joke they’ve been given isn’t as simple as it seems – how did the gooseberry get in the lift? How did it press the buttons? Why would it want to go anywhere? It’s a fucking gooseberry! It’s basically a sketch about not being able to tell a joke, delivered with terrifying conviction and a lot of violence and nipple tweaking.

The Tramshed isn’t a well-paid gig, it’s basically beer money, and we still don’t get our Variety contracts. We’re still doing 9-to-5 day jobs to keep ourselves afloat. Rik’s working in an employment agency, I’m a motorcycle messenger. It’s fair to say that the abysmal Macbeth is an absolute turkey, and the weekend show isn’t doing much better. The fiery Welshman is basically killing the venue.

We perform to a steadily dwindling audience that are getting harder and harder to please. But to be honest, it’s probably the best thing for us at the time, because it makes us focus on making the good bits work really well. We learn to hone our craft. What works, and what works really well are two very different things. We model, shape and sharpen the act until it is the shiniest diamond anyone has ever seen. Even the squaddies are laughing.

In late 1979 – when The Police are top of the charts with ‘Message in a Bottle’ – we see a message, an advert, in the back of the actors’ weekly newspaper The Stage. We read the small ads every week in the vain hope of seeing some offer of non-unionized work that we might be able to apply for. Unfortunately neither Lindsay Anderson nor Peter Brook ever slip in ads for ‘completely inexperienced and non-unionized actors who have absolutely nothing to show for themselves’, but this week it does have an advert for a new club that’s opening in Soho called the Comedy Store. It says:

Are you trapped in a boring 9 to 5 job when you are a very funny person who wants to become a comedy star . . . If your answer is ‘yes’ to that question, then contact us – The Comedy Store in Soho and become part of our Comedy Revolution. If you have the talent, we will help you to become a Comedy Star.

It’s asking for us. It’s asking directly for us.